Abinger Common, on the Pilgrims' Way, has a tradition of medieval jollity revived each year with appropriate trappings. Peter Carvell charts the progress of the 1964 event which began with a startling piece of drama. Photographs by Richard Swayne.

From Tatler magazine, August 1964.

A thousand pounds is a lot to expect in four hours, especially at a country fete. Needed are a good gimmick, good publicity, lots of hard work, no rain … and luck.

At Abinger Common they had a good start eight years ago when the rector, Dr. Chapman, and his wife revived the village’s fair of ancient tradition. Abinger sits on the Pilgrim’s Way, and for centuries the locals gave food and drink to pilgrims, who in return put on a show for them. The Chapmans revived it in medieval style: the villagers turned out in medieval clothes, some of the games in the programme were from the same period. The fete was held, as it still is, on the same green, next the same churchyard. The village still supplies food and drink, but now puts on the show as well, and asks for your money for local charities. The initial revival received publicity through John DuBois the story of Abinger reached America, and the fayre was an international success.

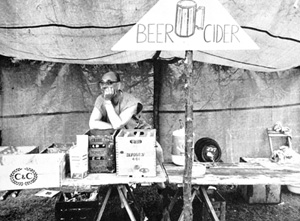

Any fete needs a lot of hard work and with people like Bert Randall around this was no problem. But what about the rain? It had never rained before and this year the committee under the Rev. Paul Kelly, the present Rector, had decided not to take out an insurance policy. On the Friday before at 9 o’clock in the evening the first thunder echoed round the Surrey hills. When I arrived two hours earlier the village was humming. Tents were going up around the village green, the arena for the riding show was being cordoned, the sheep spit was finished and there was a great clanging of hammers in every corner. Around the village some of the latecomers were collecting their costumes from Mrs. Mary Staples; some of the early guests were arriving at the manor for the weekend house party given by Mr. & Mrs. Clark, and in the schoolroom girls were practising the Maypole Dance. The front of the Hatch hostelry was getting a whitewash and, inside, the last informal meeting was being held before the great day. All the arrangements were ticked off: A.A. for signposting; the police for car parking and security; insurance against third party; Scouts and Guides to lend a hand; the local farmer to use his fallow field for parking. Crockery had arrived from Dorking. There was bran for the lucky dip; a fowl for the cockerel prize; drinks, ice and a licence for the beer stall.

The police dogs’ display team had been booked; the fee was agreed for Madame X to tell fortunes; Mr. A. Presto had agreed to give two Punch & Judy shows; the local riding school were practising for their exhibition. Handbills had been left in all the Surrey pubs for weeks before, and the district council had been persuaded to allow a banner across Dorking High Street. Every-thing looked fine.

Then at 9 o’clock the rain pelted down, the field emptied, the villagers went home to try on costumes and put the children to bed. “You get a lot of local storms here. It’ll be over in a few hours, said John DuBois. “I reckon we might make the £1,000 tomorrow if the papers give us some publicity and it keeps fine.”

Outside the Hatch the green looked as it might have done 600 years ago on the night before the pilgrims arrived; the tents wore a crown of gold, red and yellow silk and, standing under the trees by the church, I couldn’t see a house or hear a car. All evening the almost simultaneous thunder and lightning went on, people got soaked just running out to their cars, and then at midnight the lightning struck.

A triple fork flashed on to the wooden tower of the church. For two hours a human chain saved what it could in the smoke. Fire engines arrived from all over Surrey but the tower was almost completely destroyed. Abinger got its publicity next morning, but not the way it hoped. News of the tragedy brought visitors early into the village; the Bishop of Guildford arrived to look at the damage, so did the Duchess of Northumberland. The fete was now back where it began— finding money to repair the church. Everyone prayed for fine weather. The sun was out and it looked like that £1,000 was going to be needed more than ever.

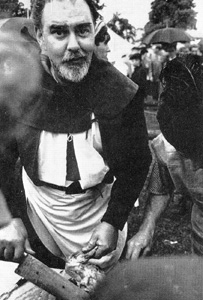

By 11 o’clock the medieval entrance gate finally went up in the corner of the field, the loudspeakers were tested and the sheep was half roasted. The stalls were nearly finished. Miss Carroll was setting up her pottery wheel and Miss Allchin her spinning wheel. An air of confidence settled over the green, until the bunting was mislaid. Half-an-hour later it was found next to the tent for the ladies’ loo.

As everyone drifted off for a quick lunch the rain started just gently. But by 2 o’clock the cars were pouring in, the whole village seemed to be in hessian and silk and the rain stopped. Dozens of girls in long calico dresses and tall Saxon hats lined up their horses under the trees for the procession. Cine cameras whirred, the horses tossed their ribboned necks and it looked like a real medieval pageant.

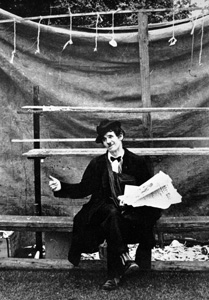

At 2.30 exactly the first rider went through the archway. The sun shone at last and the fete had begun. Already more than 1,000 guests were there to see the motley crowd of knaves and knights, barmen and barmaids, ladies and peasant girls; by 4 o’clock one would confidently expect 3,000. The fete was declared open by Mr. John Guest and the money started to roll.

The next four hours were up to the visitors. They could play medieval golf, ride a horse or try a bicycle without a handlebar. They could win an evening in London for two, knock a monk’s hat off, buy home-made jam or try to find a pound note in a honeycomb. Pent-up energy could be used to hurl wooden balls at old crockery, kick a football against a wall of balloons, knock down a giant set of skittles, or toss a sheaf of hay 15 feet in the air. lazier ones could watch the riding by local girls, police dog training by the Surrey Police, or buy a thousand things ranging from an Edward VII Coronation Cup to a book of poems by the local genius.

It didn’t matter much what they did so long as they spent money and enjoyed themselves. Noise came from the marquee and the Punch & Judy show, but the queue for Madame X was quiet and pensive. After an hour-and-a-half of sunshine drizzle returned just after four, so the tea room filled up with chattering people, hands full of home-made cakes and Victorian bric-a-brac.

After 20 minutes the sun came through again and everyone rushed out to see the tilting the bucket show. In this old medieval game it was a boy in a wheelbarrow who brought the bucket of water down on the man who was pushing him.

By 5.30 the end was near. It was pouring hard and the cars began to jerk out of the field, the stalls were packed up, the lorry arrived to take the chairs away, the lottery was drawn, the free dinners awarded and the remaining things on the stall were auctioned by Mr. Ian Frazer.

The last of the horses clopped off and at 6.30 even the ice-cream van gave up. The villagers trudged wearily off, wet and a little depressed. Within two hours the green was deserted except for the marquee full of chairs and ropes, tarpaulins and tables, flags and bunting, and Mr. Wilkins and his band counting the money.

At 9 o’clock he announced that it looked like £800 give or take a few pounds. If the rain hadn’t come at the crucial moment the fete would have made its thousand; it had had everything: except luck. But it was still the best-ever and it looked as though the church would get the money it needed, as well as all the other hospital, charities, clubs and homes who rely for their life on afternoons like this.

Abinger Common, Surrey RH5 6HZ ///delay.trials.plans

Tel: 01306 737160

Data Protection & Privacy

We do not track any browsing activity on this website.

We may sometimes link to external sites and social media but are not responsible for the content of these websites and you should refer to their individual privacy and cookies policies.

If you are included in an event photo and do not wish to be please contact us and we will remove – Contact Us

If you would like to apply for a Login account to help update this site, please email the web team here.